We waste a third of our food. What can businesses do about it?

Food systems in developed economies create an incredible amount of food waste, all along the supply chain.

With our population set to reach over 9 billion by 2040, can businesses feed people not at the cost of our planet?

So, how did we end up here?

A food system is an umbrella term for all the activities involved in producing, processing, distributing, consuming and disposing of food.

Within a sustainable food system, everybody has access to appropriate and nutritious food in ways that are economically profitable, socially benecial, and environmentally neutral or positive, to ensure the same can be true for future generations.

“Reducing emissions from food production will be one of our greatest challenges in the coming decades. - Our World in Data, an initiative out of Oxford University

Unlike many aspects of energy production where viable opportunities for upscaling low-carbon energy—renewable or nuclear energy—are available, the ways in which we can decarbonize agriculture are less clear.

We need inputs such as fertilizers to meet growing food demands, and we can’t stop cattle from producing methane. We will need a menu of solutions: changes to diets; food waste reduction; improvements in agricultural efficiency; and technologies that make low-carbon food alternatives scalable and affordable.” - Our World in Data, Oxford University,

We are exploring one of these domains—food waste reduction through a business lens, with a particular focus on the issue of food waste in developed economies. We dive into the latest global research on food waste, and hear from people in business tackling the problem.

The problem of food waste: a potted history

Chances are, you have heard or read that our food system is broken.

But for those of us living in middle-or high-income countries, this does not reflect our experience.

Our supermarket shelves are lined with an ever-increasing range of products, produce bountiful and available whatever the season. Dining out or ordering in, the experience is close to frictionless.

Food waste is the third largest emitter of carbon after China and America, if it was a country.

And “we’re planning to double our food supply by 2050 to feed the expected 9 billion on the planet, but yet wasting a third of what we produce.” - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

As we think about the problem of food waste today, it’s helpful to consider how we ended up in this pickle, as we work to find our way out of it. So, how did we end up here, wasting a third of the food we produce globally?

While saving food and preventing food waste have been central concerns for most of human history—for many a matter of sheer survival, as it is today—our story of food waste begins in the twentieth century.

In contrast to the food shortages and rations of wartime, the end of WWII was followed by widespread global economic expansion, dubbed the ‘Golden Age of Capitalism’. This period from 1948 to 1973 was marked by sustained economic growth, particularly across the United States, Western Europe and East Asia. Rates of employment and wages rose. In the food industry, innovations in agricultural machinery, storage, food processing and transportation vastly increased efficiency and lowered the costs of production.

Food waste was a victim of the economy’s success: as food cost less, and people had more to spend, food waste grew. Whereas in 1901 an American household spent just over two-fifths (42.5%) of their net income on food. About 100 years later, this "figure had dropped to one-"fifteenth (6.6%) of a household’s income being spent on food. With it, the "financial incentives for people to save and preserve food deteriorated. With such a bounty of food on offer, retailers began to enforce stringent aesthetic standards on the food they bought and sold. For retailers, overstocking was preferable to the risk of under supplying customers, and so food products past their prime would be binned.

Innovations in packaging meant that food products could be stored for longer periods, and transported further distances. But it also meant customers could no longer feel or see products as before. Enter the rise of ‘best before’ and ‘use by’ date stamping, a practice so inconsistent that by the 1970s there were more than 50 different labelling systems. For safety-conscious customers, food that had not gone ‘o!ff would be discarded due to conservative date stamping by producers and retailers.

Concurrently, convenience grew to be a high priority for consumers, with ready-to-eat meals and dining out becoming a norm. The accompanying affordability and ease of access to prepared meals further reduced consumers’ concerns for food waste.

“The general society is so far away from the production of food that you get in a supermarket. You forget that this ready meal or that bowl of soup came all from a field - farmers taking it in, worried about the rain one month and whether it’s going to be too hot the next. You forget that food is natural." - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

"And when it’s packaged up so beautifully, it’s hard to relate to, that something comes in seasons, it’s governed by weather, and all of those things that we need to make sure that farming and our food system is something that serves our planet as well."

So, our current problem of food waste has been decades in the making. In higher-income countries, while many people still struggle with food insecurity, the accessibility and relative affordability of food has created a perfect storm of consumption and waste as the value we place on food has dropped.

So much waste, so what?

“If you think about the challenges of the 21st century in relation to food, the United Nations estimates that we need to produce 70% more food by 2050 to feed a rising population... Agriculture is responsible for about a quarter of global carbon emissions. - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"So agriculture needs to go through this profound change over the next 30 years where it needs to significantly increase production and significantly reduce emissions. At the same time, it needs to do all of that whilst adapting to rapidly changing conditions as a result of climate change.”

From an economic perspective, the inefficiency of food production globally is mind-boggling. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that the financial cost of wasting a third of the food we produce amounts to about USD 1 trillion each year.

Beyond the immediate economic losses involved in food wastage, the FAO has calculated the global ‘Food Wastage Footprint’, assessing the environmental costs of food waste by using a financial proxy methodology called full-cost accounting. Over and above the USD 1 trillion "figure, the FAO puts environmental costs of food waste each year at an equivalent of USD 700 billion, and social costs at USD 900 billion.

While there are means for food waste to be recovered or recycled, landfills are still a common method of waste management. In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency estimated that food waste represents close to a quarter (24.1%) of landfills, at 35.3 million tons in a year. In Australia, the government reports that 7.3 million tons of food is wasted each year, of which 3.2 million tons - 43.8% - ends up in landfill.

Food disposed of in landfills generates methane, a greenhouse gas that is 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. For each ton of food in the landfill, 1.9 tons of greenhouse gases (CO2 equivalent) are emitted. Aside from these emissions, when food is wasted, along with it goes all of the energy, emissions, water, land use and human effort embedded in its production, harvesting, packaging, storage and transport.

The FAO’s Food Wastage Footprint calculations of environmental and social costs illustrates “the market distortions in the global food system.”

The immediate financial costs and gains of producing, selling and wasting food are not the only economic considerations. The FAO’s assessment shows that the way our current food system is built to operate is economically inefficient and environmentally unsustainable.

The what and how of managing ‘food waste’

The concept of ‘food waste’ itself is problematic. We hear the word ‘waste’ and think of it as “uncomplicatedly the rejected and worthless stuff” at the end of a linear process of production, consumption and disposal.

The ways we manage our waste mean that the problem of food waste is largely invisible to most of us, as we don’t have a window into each step of the food supply chain, nor do we tend to give a great deal of thought to the food we waste as individuals or households, after we dispose of it.

The waste hierarchy is a common tool for evaluating which processes are most or least preferable for protecting the environment and our use of resources. From a food waste perspective, the hierarchy is as follows, from most preferred to least:

The waste hierarchy maps a linear process, and doesn’t account for circular economy solutions like the Goterra system we explore later. That said, it does make clear the priority to prevent the amount of food going to waste in the first place, and focus on utilising food for human consumption as much as possible before resorting to other options.

The reasons for food being wasted are numerous, and occur all along the supply chain:

“Most farmers will have an idea of what the demand will be for their second crop in the year, and then the weather flips it and now they have a bad crop. Some will simply be thrown away because the price is not good enough to bother harvesting it." - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

"And then there’s the shape and the size - the specifications on produce. Normally on fruit and veg, but it also happens on eggs, for example, and a lot of other different crops.

In manufacturing, there’s a lot of waste: if you’re turning on and off a production line, or you’ve got fresh produce and you don’t know what the demand again is going to be in your planning. You’re often having to start making an order three or four days before the order is due and the demand might change.

In the actual retailers, it’s very hard for them to manage supply and demand of what’s going to sell and what’s not. Sometimes, just to make the shelves look full and abundant and make people feel like they want to pick that product. One lonely melon often doesn’t do it!

In restaurants as well, you’ve got the food waste on the plate, and then out the back trying to understand what the demand is going to be for different things on the menu and wanting to give the consumer choice. And then in our own homes. So it happens in so many different places.

There’s also then the global food supply chain, where you’ll be growing rice and putting it onto a global market. Sometimes western countries might be demanding more than they actually need and taking more out of the global supply chain."

A breakdown of global food waste

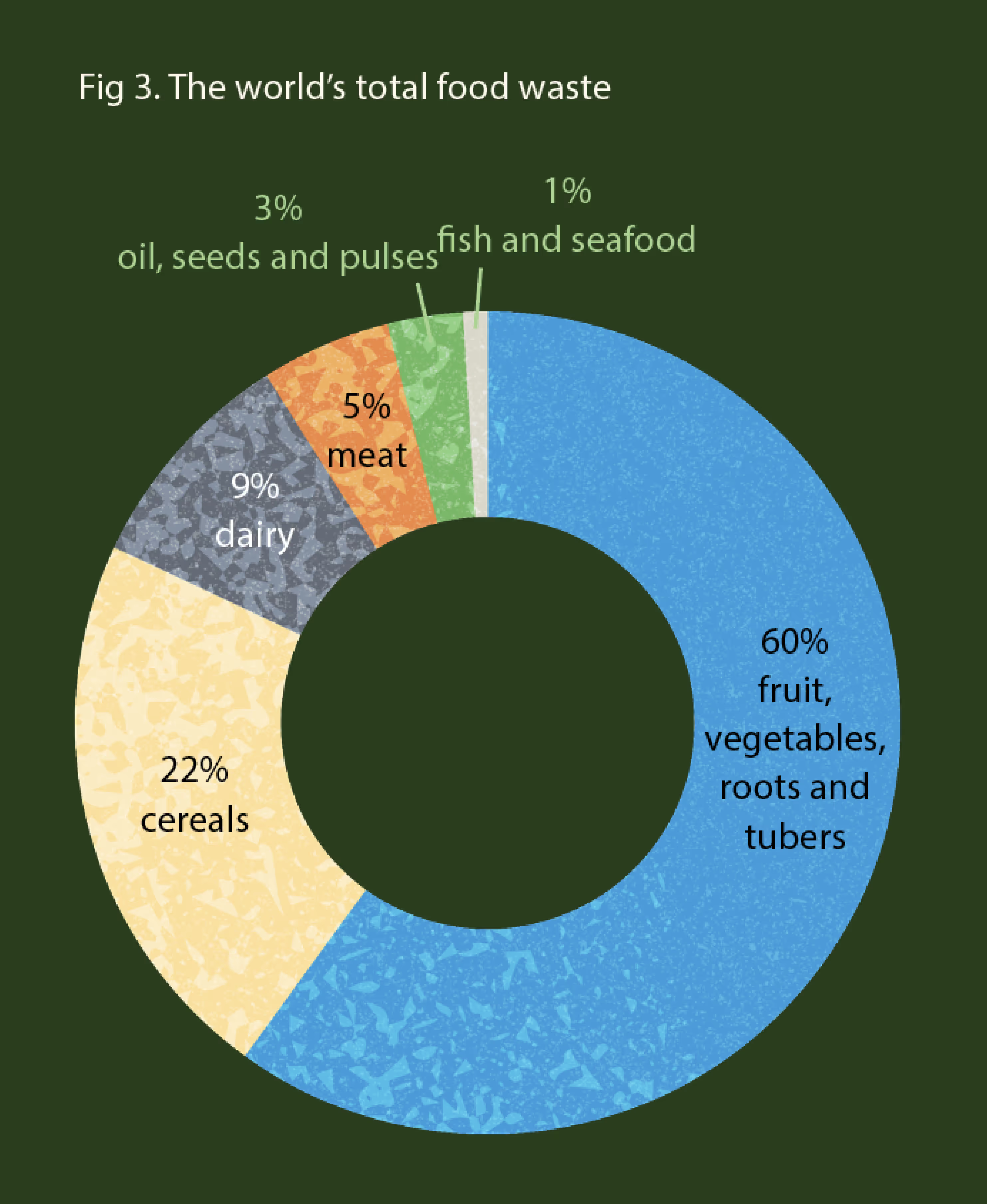

The world’s total food waste is made up of 60% fruit, vegetables, roots and tubers, 22% cereals, 9% dairy, 5% meat, 3% oil, seeds and pulses, and 1% fish and seafood.

Within food categories, the UN Environment Programme estimates that globally, somewhere between 40 and 50% of fruit and vegetables that are produced are wasted, close to a third (30%) of cereals are wasted, and a "fifth of meat and dairy is wasted, and 30% of fish.

While our first impressions of ‘food waste’ may be that it is food not to eat and of little value to us, research based on the UK found that three-fifths (61%) of food wastage is avoidable and could have been eaten if it was managed differently.

The business forging a different path

The businesses we hear from work in different ways to repurpose and recover food that was otherwise headed for waste, or take food wastes that are seen to have no value, and create value from them through repurposing them in innovative ways.

We show how businesses in the food industry do not need to be just another cog in a broken system. There is an opportunity to be part of the solution, while turning a profit. Contemplating the sheer scale of food waste globally can be overwhelming. The good news is there are a lot of sustainable food businesses emerging, and established food businesses retrofitting more sustainable solutions to the problem of food waste.

Take Rubies in the Rubble, a sustainable food business creating condiments like ketchup and mayonnaise from ‘food waste’, stocked in major retailers and venues across the UK; or DC Central Kitchen, a social enterprise running a catering business and charity to rescue food and help people with barriers to employment in Washington DC.

We hear examples from large established businesses, including Nando’s, that have introduced programs to prevent food waste, and from innovative startups such as Goterra and Glanris, taking post-consumer food waste and rice husks, and turning them into valuable resources.

While small and medium businesses alone can’t tackle the complex problem of food waste that has built up over decades, they can pave the way in restoring the value we place on food, and demonstrating sustainable means of producing, processing and recovering food.

The diffusion of innovation

“I really like the idea of the diffusion of innovation. You have innovators and early adopters who make up about 16% of the market. Then you’ve got the early majority at 34%, the late majority at 34%, and laggards at 16%." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"There’s a real opportunity for smaller players in the market to disrupt by being innovative. The challenge you’ve got is getting above 15%. I personally have moved on from Nando’s to go and work for a startup that produces insect protein o" food waste, because we need to find alternatives to soya [to feed chickens]. Insect protein is a very sustainable way to do that.

I don’t expect that we will disrupt the soy market anytime in the immediate future, because it’s going to take a long time to change all of those embedded systems and to do so at scale. But as a startup, we will work with innovators and early adopters in this space who are interested in doing something really progressive and really exciting, and being part of the change they want to see in the world. And we will ultimately see that change, but it will take time.” - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

Startups and businesses like Goterra or Rubies in the Rubble provide templates for what a different relationship to food can look like - but they can’t solve the problem alone. They are part of a new economy, and a lot needs to be done to get them to scale. It will take the biggest food producers, manufacturers, retailers, and government regulation, to move us in the right direction.

We are seeing early signs that the need for a more sustainable food system is shaping some big business practices too.

“Whether it’s 5, 10 or 15 percent of companies who are really pushing the boundaries, I think we’re seeing change happen quite quickly now. And I think we’ll see that pace of change accelerate." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

Nestle, the biggest food business in the world, has its share of controversy. However, they recognise an expectation to be publicly accountable for their commitments and progress in food waste management. In June 2020, Nestle set a target of a 50% reduction in operational food loss and waste by 2030, through the ‘Champions 123’ initiative. Champions 123 has called on ten of the world’s food businesses to engage at least 20 of their suppliers to reduce food loss and waste by 2030.

In their 2020 progress report, Nestle states that 95% of their factories have reached “zero waste for disposal status”, while all their factories have waste diversion processes in place (with 5% not yet at 100% zero waste for disposal). For companies such as Nestle, operating at such a scale, the complexity of the business is exponentially greater than startups where sustainability has been baked in from day one. At the same time, the influence and reach of a company like Nestle means that even incremental decisions can create a big impact.

“When you look at some of the biggest corporations on the planet (20 years ago, I never would have thought that I would be praising the biggest corporations on the planet!)..." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

But you look at the likes of Unilever, who are really pushing to build genuinely sustainable, large scale businesses that are able to have significant impact. And then there are operators throughout the middle tiers that are the same. It’s the diffusion of innovation.”

Like Nestle, global manufacturer Unilever has made a number of commitments to improve their practices through the ‘Champions 123’ initiative, including a commitment to “Halve food waste in our direct operations from factory to shelf by 2025”, bringing forward the original target by 5 years. As part of this, they are rolling out standardised reporting on food loss and waste across the countries where they operate, and have signed the Consumer Goods Forum commitment to switch to standardised food expiry dates by 2020.

Low hanging fruit: applying tried and true approaches in fresh ways

Think about redistribution

Case study: How Nando’s redistributes millions of meals for people in need

Bob Gordon, in his previous role as Head of Sustainability at Nando’s in the UK and Australia, led social and environmental programs with a view to reducing Nando’s impact, engaging staff (‘Nandocas’), and improving the service and brand for customers.

“The hero project, both in the UK and in Australia, was the work we did redistributing surplus chicken to people in need. We set up local relationships between local restaurants and local charities so that they could donate chicken that would otherwise have gone into the bin." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"And that just ticked all the boxes. The Nandocas hated throwing chicken in the bin at the end of the night, they loved putting it in the freezer so that it would go to a good cause. There’s a social angle of people getting fed good nutritious protein and the environmental angle, that chicken wasn’t produced and then thrown in the bin, it was produced and then eaten.”

For Nando’s, the early success of the program, which has now seen millions of meals redistributed, rested on developing traction internally among the team, and addressing the practical challenges of the program through a pilot phase:

“If you can make things easier for the team, save money and save the environment... It’s when you find something that does do all of those things—and those things do exist—you get a lot of traction really quickly." - - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"But on the flip side of that, when you don’t tick all three of those boxes, you can meet a lot of resistance, and things can be really hard. Achieving changes is a really hard thing to do. The same rules apply to any other program, you need to get some buy-in and go through a proper trial. Be really fair about the way that you operate the trial and the way that you assess that trial. Present that back in a way that’s really fair. Get more buy-in, expand the trial, go to the next stage.

So it’s project management. I would say that the very first step in all of that is about getting emotional buy-in from people because there will be hurdles. And when you have emotional buy-in from people in the team, then they’re prepared to stick with you.”

Nando’s had to assess the added time, training and resources it would take to roll out a food redistribution program. Taking an honest look at the potential hurdles, developing a system that was as straightforward as possible for team members to implement, and developing internal buy-in about the social and environmental benefits of rescuing food, has led to success in these cases.

Case study: The business wins of donating food with DC Central Kitchen

Businesses partnering with food rescue operations as a way to prevent avoidable food waste is a relatively common practice. In many cases, businesses that donate excess food products are able to claim a tax deduction on the value of goods, making this a more financially viable option than dumping stock.

However, many businesses are averse to donating food, believing that they will be held liable if a recipient falls sick.

“There’s never been any liability concern. It’s probably one of the greatest urban myths almost globally, because you hear this constantly, even today. - Robert Egger, Founder, DC Central Kitchen

"Media channels were coming to the kitchen every day. And a big part of my responsibility was trying to say, ‘There is no law that says you can’t donate food.’ But initially, when President Bill Clinton was elected, we had a Secretary of Agriculture named Dan Glickman. He really was upset about the amount of food that we were wasting in America.

At the time, there had never been any studies [on the scale of food waste]. So we embarked together on both a study of the issue, but also this issue of a national law. In 1996, Bill Clinton signed the Food Donor Act of 1996, which was the first time we created that same liability protection that exists now.”

There are express provisions built into legislation in the USA, the UK, and Australia, as examples, that protect food donors from liability if the food has been donated free of charge and is safe to eat at the time it was donated, as well as that instructions are given if particular storage is required. As Robert Egger explains, one of the strongest barriers to businesses donating food for human consumption simply does not exist.

Robert Egger founded the DC Central Kitchen in Washington, DC in 1989. Set up as a social enterprise, the Kitchen collected donated food from producers, restaurants and hospitality services, which they would prepare and serve free of charge to people in need. At the same time, DC Central Kitchen would purchase food that was ‘out of spec’ at a lower cost, and train people with barriers to employment for careers in the food industry, running a catering business and cafe.

Before ‘social enterprise’ was a common idea, Robert Egger recognised the power of business to create positive social changes in his city and create a more equitable food system.

“I ran nightclubs as a young man. I went into the nightclub business intent on learning everything I could about the business in particular... and that demands a very, very deep scrutiny of your cash." - Robert Egger, Founder, DC Central Kitchen

"In learning about nightclubs and restaurants and catering and the variety of different aspects, I learned how much food was thrown away every night by people who love food. It’s not like they were laughing and throwing legs of lamb in the dumpster. They hated throwing away food. But as businesses, they were concerned that if they gave out of generosity, they didn’t want that generosity returned with a lawsuit if somebody got sick.

I was aware of this, and I went out one night, with no real intent on doing anything more than having a volunteer experience, feeding poor people who were sleeping outside in Washington, DC. We drove around that night by the White House, by the World Bank, by the Smithsonian Museum, feeding people.

But I was upset because I witnessed in effect a charity model based more on the redemption of the giver, not the liberation of the receiver.."

"And I just thought, wow - if you could collect from the restaurants, the hotels, the caterers, the hospitals, farmers, food that they hate to throw away and make sure it’s handled professionally, you could feed more people better food for less money." - Robert Egger, Founder, DC Central Kitchen

"If we started a cooking school, you could feed twice as many people, and you could shorten the line by the very way you served it because you’d be offering the chance for people to come out of the line to be part of the solution versus endless recipients of charity.”

The kitchen opens

After approaching existing charities with this social enterprise concept and being knocked back, Robert opened DC Central Kitchen in 1989 with a bang:

“Much of business is marketing. I opened up the DC Central Kitchen on January 20th, 1989, which was George Bush Sr’s inauguration. I called up the inauguration committee and said, ‘Hey, you’re gonna have these big parties, you’ll have tons of leftover food. Let’s do each other a favour that makes you look good. I’ve got a new refrigerated truck, let’s do business.’ - Robert Egger, Founder, DC Central Kitchen

"And so on opening day, we had media from around the world wanting to cover food going through the inauguration celebrations to a kitchen and feeding people the next day. And that set the framework for the kitchen as being an open source business that would constantly innovate, but also share whatever we came up with.”

By taking a business approach to the problem of inequity in access to food and employment, DC Central Kitchen were able to partner with businesses by demonstrating the economic benefits of food rescue:

“I work on the business mantra of quid pro quo, both sides benefit. And so whenever I worked with somebody, it was always like, I got a deal for you. I’m going to give you something you need.

"So for example, when I went to restaurants, I said, ‘I am going to cut your trashbills in half. I will cut your waste control. I will give you a tax deduction for what you’re doing.’ And I’ll help you improve staff morale, because they’re going to be thrilled. They’re not throwing away perfectly good food anymore. And I’ll use that food to train somebody who can now come to work for you and help you make more money. Because at the end of the day, my business was how do I make my city, Washington DC, a better place to live for everybody.”

Look to repurposing

Case study: Rubies in the Rubble and the power of preserving food

“And you’re telling me you got an enormous amount of tomatoes that are being wasted, and I guarantee you somebody’s buying ketchup. Do that deal! Come on.” - Robert Egger, Founder, DC Central Kitchen

Rubies in the Rubble is a sustainable food business based out of the UK. They produce a range of condiments including tomato ketchup, mayonnaise and relishes made from food that otherwise would have gone to waste. Started by Jenny Costa in 2012, Rubies in the Rubble supplies their products to some of the UK’s most recognised retailers and restaurants, including Waitrose, The Co-operative Group, Morrisons and Honest Burgers.

“I started Rubies in 2012. Going right back to my childhood, I was brought up on a small farm on the west coast of Scotland and sustainability was really at the heart of our upbringing." - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

"We had a well for collecting our water, we created our own electricity from wind turbines and my mother used to pride herself on feeding the whole family from her veggie garden. And so preserving fruit and veg and the old fashioned way was something I was really aware of.

I was coming back from work one day, and I read an article about supermarkets locking their bins and people trying to get in to take food that was perfectly good but past the sell by date. I was thinking, food is perishable, it’s governed by the weather, which is unpredictable. And then at the other end, it’s governed by us and our demand, which is also unpredictable. And in the middle, these giant supermarkets are showing everything in plentiful volumes."

"With it being perishable, what happened when that supply and demand didn’t add up?” -Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

Extending shelf life

Rubies in the Rubble took its cue from millennia-old practices of preserving food to extend its shelf life and add value to produce that is not fit for the high aesthetic standards of supermarkets, or doesn’t have the shelf life for transporting to and displaying in stores.

“I started with chutneys and relishes. I would team up with farmers whenever they were doing a crop tip of apple or pears. Often a farmer normally on average could waste between 20 and 40% of that crop." - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

"So I’ll take things that are undersized, oversized. Sometimes, if it’s a cherry tomato that has a short shelf life, or they’ve got too much and the demand for it wasn’t realized, or if it fails that test and that prick test of the 15 day life, we’ll take it.

We can turn it into a relish that then adds a two year life on it and adds value to the tomato. So traditionally that’s how we’ve done our chutneys and relishes. For our ketchup, we’ve actually created a pear puree made from surplus pears. It replaces half of the sugar in the ketchup, because we realized that sugar and water were the main ingredients.”

As well as repurposing avoidable food waste to add shelf life and value, Rubies in the Rubble have utilised other types of potentially avoidable food waste to create new products in their line.

“We have plant-based mayonnaise based on aquafaba, which is a byproduct of cooking chickpeas. It has the same properties as egg whites. So we’ve teamed up with hummus manufacturers. And when they cook their chickpeas, they normally throw away that water. We collect that water, turn it into a powder so it’s in an ambient state and then use it for our mayonnaise.” - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

Unlike traditional food businesses, Rubies in the Rubble first considers what types of produce are generating greater amounts of waste, and then looks to develop products that use them in a way that appeals to consumers. Rubies in the Rubble’s banana ketchup demonstrates this alternative approach to developing new products:

“Our banana ketchup is really a ‘Marmite’ kind of product - people love or hate it. Bananas are one of the most commonly thrown away fruits in the UK. They’re very hard to get rid of as well, because you can’t put them into anaerobic digestion." - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

"They’ve got a huge carbon footprint. They don’t decay very well.

At first we developed it as a chutney. It had a really small following. We launched it on Ocado and a couple of other places. At one point, we thought, ‘we’ve got to take this product off the market. It’s so small and growing so small compared to the others and people just don’t get it.’

We delisted it and got this flurry of emails from people just furious that we had! So we got about 250 people to send feedback on how they use it, what they eat it with. Most people were having it with a salad that would make it almost Caribbean, or they would serve it with curries instead of a mango chutney. Or they’d put it with a chicken burger.

So we decided to get it out of a little chutney jar and put it into a bottle and call it a ketchup. Since then it’s stayed with us and it still is a sort of a funny old product that people either love or hate! But it definitely showcases what we’re all about in a really interesting way:"

"…taking an ingredient that was a waste product, and really trying to find a demand for it.” - Jenny Costa, Founder and CEO, Rubies in the Rubble

A simple yet effective solution to food waste

The Rubies in the Rubble story reveals that repurposing food products that would otherwise have gone to waste, and finding new ways to repurpose them and market them to customers, can create a distinctive and profitable business.

What we see is that business solutions to the problem of food waste don’t necessarily require the latest technologies or innovations.

Looking to longstanding human techniques of prolonging the life of food through preservation, Rubies in the Rubble has created a sustainable range of products that add value to ‘out of spec’ produce, meet consumer demand, and create a point of difference in the retail and hospitality space.

Space for innovation: new applications for transforming food waste

Applying technology

There are some forms of food that are harder to manage.

Unavoidable food waste is represented at the bottom of the ‘food waste hierarchy’, and is thought to have the least value. Unavoidable food waste consists of elements of food production that we would not normally consider edible, such as meat bones, egg shells, or co!ee grounds.

In these cases, the opportunities for businesses often lie in developing new technologies and systems that are able to process these forms of waste and create value from them.

Case study: How startup Goterra combines bugs and tech to turn trash into treasure

Post-consumer food waste from retail and hospitality venues is a complicated mix of avoidable and unavoidable food waste, and one of the most difficult to divert from landfill.

“Goterra’s business model is founded on managing really hard to process wastes. What we don’t want to do is skim off the easiest to manage wastes off the top, because then we haven’t really affected change." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"We want to find the really hard to manage waste and produce a material that can go back into the food supply chain… take low grade wastes that can’t be used for anything of higher value and valorize them. If we’re doing that, we’re actually genuinely creating a circular economy.”

Goterra is a business using insects to sustainably process food waste and create high protein chicken feed. Goterra has created a waste management system that is able to process this post-consumer food waste and create value, converting it to a sustainable protein for chicken feed.

How Goterra’s system works

They do this by installing a robotically managed unit called ‘MIBS’ - Modular Infrastructure for Biological Services (by all appearances a high-tech shipping container) - onsite at a venue where food waste is generated, say, the basement of a shopping centre or hotel building.

Food waste can be tipped into the unit, where black soldier larvae - maggots, to be frank - feed on and naturally process the food waste. The black soldier flies are essentially ‘farmed’ on the food waste, and can then be sold as protein-rich feed for chickens.

“We’re taking low value waste that at best will be used to produce soil." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"Particularly with post-consumer food waste, it’s got lots of stuff that’s not particularly good for composting, like meat and dairy and citrus. And it’s got lots of contamination. If you pull food out of a food court in a shopping centre, there’s loads of bits of plastic that you don’t want going into compost.

Whereas our insects eat around all of that. Then at the end of the process, we sift it, and it shakes it all off. So we’re able to handle these materials that aren’t useful to anybody else and put them to really good use. And that’s where we’re creating the circular economy.”

As opposed to alternative food waste processors, like electronic food waste digesters - which process food waste to extract water and push this through existing wastewater management systems to be processed - Goterra creates a high value product off of food waste, without the need for integration into existing waste management logistics networks.

Taking waste management to the site

“There are other systems that eliminate the movement of waste, but typically, they will either pump the material down the drain, which isn’t particularly environmentally friendly, or at best they will produce some kind of soil product." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"What we’ve done is designed a technology that enables us to decentralize waste management. So existing waste management systems rely on large scale operators, typically further out of town, and then a logistics network that supports that.

If we’re able to take the waste management infrastructure to the site where the waste is managed, then we can be far more e!cient and then treat it in a really e!cient and sustainable way. We can be far more efficient in the way that we manage our wastes. And we can also get more value locally from those wastes through producing food [for animals].”

For Goterra, the innovation lies in marrying up an age-old natural process - using insects to process organic waste - and modern robotic technology that monitors temperature, humidity, and controls when to move waste from the internal receival tanks to the larvae, ensuring a healthy environment for the insects.

“This is a wholly natural process. Insects are nature’s cleaners. And all we’ve done is and a way to put those cleaners in a place that enables us to derive some benefit from it in the way that we operate our societies. We’ve done it through a modern lens of building robotics and systems that can enable us to extract value from that in our economies.” - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

Thinking back to the waste hierarchy, Goterra is taking food waste that falls into the fifth category - unavoidable waste that would otherwise go to landfill - and moves it up the hierarchy to the third category - producing animal feed. As a result, they create a circular economy that turns a low-value waste stream into a higher-value food product.

“A material that would have been down-cycled into a lower grade product is now used to produce additional protein, local to the place that the food waste was produced. We’re doing that with really no emissions.” - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

As is often the case for businesses that are innovating and turning existing processes and services on their head, Goterra’s current challenges lie in changing the way businesses understand food waste management services, and winning decision makers over to a new model.

“There’s a lot of interest. We’re working with waste companies, food, retailers, hospitality, councils, shopping centre managers, hospitality, other institutions." - Bob Gordon, Director, Zero Carbon Forum

"The challenge we have is about changing the system. It takes time, whether it’s for a waste management contract to be up for renewal, or for the right people in the business to have the time and bandwidth to really consider whether or not this is the right thing for them to do. And then it takes time to explore that, and to look at all of the operational and logistical challenges to make it actually work.”

Case study: Using rice hulls for water filtration with Glanris

Shifting now to the other end of the supply chain, in the agricultural production of food, there is one waste product that overtakes the rest: rice hulls. Rice is the staple food for more than half the world’s population, but the outer casing of rice grains, called the hull or husk, is inedible and removed during harvesting and processing.

“About 20% of the harvest of rice is the hull itself, which has no nutritional value. Most people burn it in the fields, which produces almost a trillion pounds of greenhouse gas every year. - Bryan Eagle, CEO, Glanris

"So what we’re on a mission to do is to stop them from burning it in the fields. We don’t burn it. We pyrolyse it, which means you cook it in the absence of oxygen. It doesn’t release carbon dioxide and methane; instead you convert it into a stable carbon format.”

Bryan Eagle is the CEO and Founder of Glanris, a startup based in the US that has created a new use for this abundant waste material:

“Glanris is Gaelic for ‘clean rice’. What we’re doing is we’re taking the world’s most plentiful ag waste product, which is rice hulls, and converting it into a water filtration media that can help to clean up water around the world." - Bryan Eagle, CEO, Glanris

"It’s a new application of an old technology. A lot of people call it biochar. For the past 40 or 50 years, it’s been used mostly for soil amendment, because it holds onto water. The problem with that application is that they weren’t using as much of the ag waste as is generated. A very small percentage of the ag waste that’s generated actually gets used for soil amendment. And typically in that environment, it’s not a high value additive for the farmers.”

The process of turning rice husks into a water filtration material

Glanris has created a new process to turn these rice husks into a higher value water filter material that is environmentally sustainable and more affordable than existing solutions.

“The breakthrough for us was to take a look at other novel applications for this. By converting rice hulls to a stable carbon, you can activate it. Activated carbon is like a sponge. - Bryan Eagle, CEO, Glanris

"If you have a Brita filter in your home or pitcher based systems, what’s in there is activated carbon, to pull out the chlorine and take out the odour, and a lot of the things that affect the taste of the water.

What we figured out how to do was to add an additional capability to that basic carbon structure, to be able to pull dissolved metals out. So now, we can not only pull the organics and chlorine out, but we can also deal with lead and copper and other dissolved metals that are in the water."

Practical applications

"Again, if you open up that Brita cartridge and you spilled it out, about 60% of what’s in there are these tiny little petroleum-based microplastics, that are used to pull out those metals. It’s not good for the environment." - Bryan Eagle, CEO, Glanris

"What we’re doing is developing a sustainable process that is made from ag waste, and is able to do the same thing. It removes organics and it removes dissolved metals in a very economical way.”

As is the case with Goterra, the challenge for Glanris lies in encouraging industrial businesses, municipal governments in charge of water supplies, and household consumers to adopt this new "filtration system and depart from their existing processes and suppliers.

“In the industrial space, they’re always interested in technologies that are going to save them money. The hurdles that we’ve already seen in early discussions with the municipal folks is that they’re very reti- cent to adopt new technologies." - Bryan Eagle, CEO, Glanris

"They are risk averse, and for good reason because if they mess up your water, people get sick. So they don’t take risks. They like to see stuff tested and tested and tested and tested. That path through pilot programs and repeated testing is sort of the death march for lots of startup companies. You just can’t get to the other side and get to the point of making revenue.

So right now we’re focused on the industrial market. We’re building up our use cases. We show that it’s working, that it has efficacy. They’re able to look at the payback back analysis on that application.”

For businesses and entrepreneurs looking for a context to work in, the need for innovative approaches to food waste diversion and recovery across the food supply chain presents a big opportunity.

While they are in their early stages, both the Goterra and Glanris businesses indicate some of the potential scope that lies in finding new applications for technologies to sustainably process unavoidable or hard-to-manage waste, and create higher value goods and services through this.

How do we get out of this pickle?

At the simplest level, food waste comes at a big cost: not only financially, but also environmentally and socially. To varying degrees, we are all part of this mind bogglingly in ancient global food system.

As we’ve found through these case studies, there are businesses solving this problem using tried and tested methods that are well within our reach. Here are some actions for businesses to get out of the food waste pickle:

Ready to redistribute?

1. What have you got to give?

Assess the amount of food that you have in surplus. Keeping good data about the product types, quantities, lifespan, ingredients, cost value, retail value, locations will help you and your chosen redistribution partner to maximise the value of that food.

Determine how often you have a food surplus. Is it a once-off (e.g. from a large event, an ordering error, a forecasting error) or a more regular occurrence (e.g. overproduction as a result of ongoing demand fluctuations)?

2. Partner up

Research organisations in your area that redistribute food. These can include nonprofit food rescue organisations that collect surplus food and provide it to local community food programs, or commercial food rescue organisations that take bulk ingredients and other food products and list them to wholesale at a heavily discounted price.

Clarify logistics: transport and storage, any safety requirements. Find out what the "nancial bene"ts may be available to you. In some contexts, tax deductions are available for donated stock according to its retail value.

Looking to repurpose?

If you run a food wholesale or retail business, there may be opportunities to develop new product lines using food that may otherwise go to waste.

If you are a primary food producer, there may be opportunities to partner with a wholesaler or retailer to find a new market for surplus food, or even food production byproducts that have traditionally been seen to have limited or no commercial value (e.g. aquafaba, the water used for cooking chickpeas, as a vegan alternative to egg whites in mayonnaise or even meringues).

Research to find out if there is a potential market for this product. Are there new products to create or modify? Does your business have the capacity to develop new products, or is there an existing food product company you could partner with?

Apply technology to find new solutions

For businesses producing inedible food waste or agricultural waste, new technological applications are providing ways to create value from what has previously had limited or no commercial value.

Are there existing initiatives (the likes of Goterra and Glanris) that your business can connect with, to transform your existing food waste? Find out what circular solutions are emerging.

While in our current system, it may not be possible to completely eliminate food waste, businesses approaching the problem with an attitude of ‘progress over perfection’ are yielding outcomes that are good for business and for the planet.

.png)

.png)